Context before we get into it

This one is going to be hard to talk about. There’s a couple things that we should talk about before getting into what is Pico-8 and whether you should get it for yourself or your kids.

Classic consoles and their limitations

Graphical fidelity

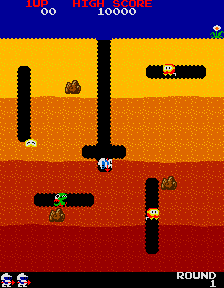

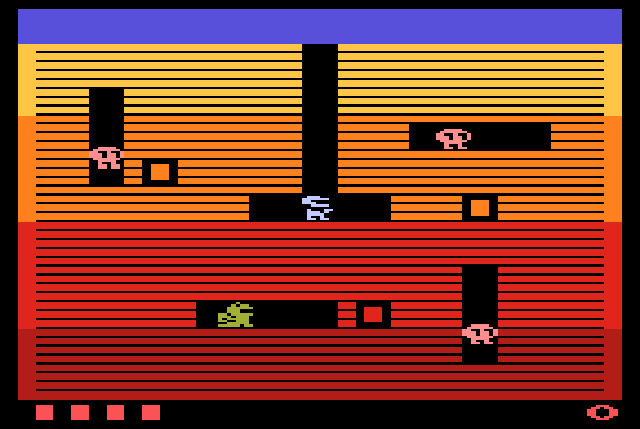

Go back to the 1980s. Computers are still mostly for the big businesses, but some where starting to get into peoples homes. TVs were well established in everyone’s homes, and have been seeing various game consoles being attached to those TVs to play extremely abstract Video Games. Games like PacMan and Galaga started the decade in the arcade really strong. However, these quarter munchers used high-end hardware and needed the extra physical space and dedicated chipsets to properly render and run the game at full speed. Consoles from the likes of Atari worked for home markets, but could at best produce extremely simple geometries which required a lot of imagination to fill in the gaps. Often developers would attempt to make home console versions of arcade games. One example includes the Classic Dig Dug. Checkout these screen shots from the Arcade version beside the Atari 2600:

It works to get the same point across, but clearly you don’t have a lot to work with as far as recreating the picture.

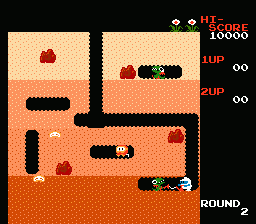

In 1983, the Nintendo Family Computer (Famicom) was released released in Japan. This home console finally came to the United States in 1985 as the Nintendo Entertainment System (NES). This console game with a huge gap in graphical power, allowing developers to create much more detailed sprites, environments, and I’m sure game mechanics. To keep the the examples consistent, Dig Dug was also released for the NES.

We can see that, while not quite as nice the arcade port from 1982, it is much clearer than the version from the 2600. This could be a thoughtful gift for someone who has already played the arcade port and wanted to bring it home.

I feel that the important history lesson to be gathered as we follow graphical progress of these games is that Developers always build games to the hardware that is available at the time. If you want your game to be played, you need to make sure people will want to buy it, and you make them want to buy it by producing the best possible version of your game for the specific hardware you are making the game for. The Atari 2600 version looked the way that it did because that’s what the console was capable of, not because the developers were unskilled. This is critical to remember moving forward, as this idea will come up multiple times.

The transition to 3D

Take a more modern example: in the 1990s, we saw the release of the Nintendo 64 and Sony Playstation (and that other one from Sega that most people probably didn’t play). This was the first generation of home consoles that was able to render three-dimensional graphics. The hardware (specifically the chips) finally were fast enough to perform all the mathematical operations needed to

- define the three-dimensional space,

- compute the geometry of everything in that space,

- map the appropriate textures and images onto that geometry,

- and finally convert that three-dimensional space to a two-dimensional image that gets sent to your TV.

While some games before the ps1 and n64 were able to produce graphics that felt like 3D. The difference between these games and the ones on later consoles is the tricks used to force a 3D perspective, rather than a 3D environment. Two promonant examples of 3D games before the mid-91s include

- Doom, which originally a PC game, was ported to all sorts of home consoles. This game defines it’s levels on a 2D plane, then uses some very specific math to render the textures and shooting physics into a 3D space (though, I did fine this video arguing it is a 3D game very interesting). This 2D engine and restrictions were imposed to ensure the game ran lightning fast on PCs from the ’90s.

- Many mode 7 games on the Super Nintendo Entertainment System (like Super Mario Cart or F-Zero) were able to force a perspective that appeared like the camera was right behind the player, and the world was going off into the distance. However, once again, everything was defined under 2D backgrounds and tiles with tricks and math layered on top to force that perspective. Check out this video for a further exploration of how Mode 7 specifically worked.

Games looked better when I was a kid

For a final example of the point I want to get across, consider the television set itself (or monitor if you’re part of that PCMasterRace). If you are around my age, you likely remember the first “Flat Screen” TV your family got. It was probably this massive “widescreen” panel that was just a big in the back as it was wide in the front. It definitely had about 4 or 5 composite and vga ports in the back to plug in the cable box, the DVD player, and your favorite console of the generation. Ours was around the time we had a PS2 in our house. When that happened, we moved equally heavy, but significantly smaller CRT upstairs to our shared play area which was also kind of my bedroom (I chose to live in the loft). Two vastly different forms screen technology: the LCD panel (or Plasma if you were in that camp) and the CRT. Once generated images from the back of the screen, one from the front. One had to be curved to display without distortion, one could be flat. One had scanlines and would only display “interlaced” images, one introduced High Definition and progressive scan images. One seemed obsolete, and the other was the future.

Fast forward a decade or two, and let’s imagine you wanted to play the Sega Genesis version of Sonic 3 and Knuckles to be greeted with these chunky pixels.

Now, don’t get me wrong, I love classic Sonic and one of my favorite modern games is Sonic Mania, but there is something about some of these images from games past that lack a certain bit of depth. The pixel are is great, but something is off a little bit.

Once again, you need to remember that these developers from the ’90s and earlier were not developing games on or for fancy new flat screen LCD panels with millions of pixels on them. They were using CRTs and developing individual pictures that may have been 16x16 pixels to put into their game (yet another video you should watch.) This one recommends specific shaders and tries to walk you through the process of setting up this CRT effect. I mostly would like for you to focus on the side by side images at timestamp 6:40. The first image is what we are actually producing on the computer. The second two are images that have post-processing added to them to recreate what the image would have looked like on an old school TV. Notice how the addition of the black between the pixels and the softening the edges creates colors between the actually blobs of color that are filling out the full picture.

I’m not here to make a claim as to which one is better. Some people really like their sharp pixels, I’m personally in the camp that likes the shaders when I play retro games. I will absolutely let you have your opinion, but when the developers made the games, they not only made the games not only the console hardware, but also the screens available at the time.

Another example of this phenomenon is the fall of Light Gun games. CRTs are able to change their images at a much faster rate than an LCD ever could. This functionality was utilized produce entire genres of games that have since fallen to the wayside as we moved to new display technologies. Here’s a whole retrospective on the history of light gun games.

Closing out this soap box

The entire point of this entire prologue is the following: developers built games to the hardware that was available at the time. In these earlier classic games, they did not have the supercomputers in our pockets and laptops in their bags. Processing chip speeds were much slower than they are now. Memory stick sizes were much smaller than we have now. The interfaces available to players were vastly different. Developers worked within their limitations of their times to build the best games they can. We had fun with these games. Games don’t need to have the 8K resolutions at 120 FPS. They don’t have to have photorealistic graphics or high resolution textures. If it’s got a good control scheme and engaging, it has the potential to be tons of fun. For proof, check out these releases of 2025

- Silksong: the long awated sequel to Hollow Knight, both massive hits.

- Megabonk: a meme game, that will likely not live past this year, but topped the chars for a bit.

- Escape from Duckov: A game where you play as a duck that shoots guns in a apocalyptic wasteland.

- Fortnite: though not released in 2025, it’s still a massive hit, floating around 1 million players daily.

Old games are fun. Small games are fun.

A case for Pico-8

I feel this context is important above because Pico-8 is really an entirely different experience than any game or software that you would pick up on steam. It doesn’t work like the modern games with their current conveniences. Understanding some of the history of games is important to keep in mind when diving into the experience that is Pico-8. Let’s start with why you should give it a try.

Why you should get and play Pico-8

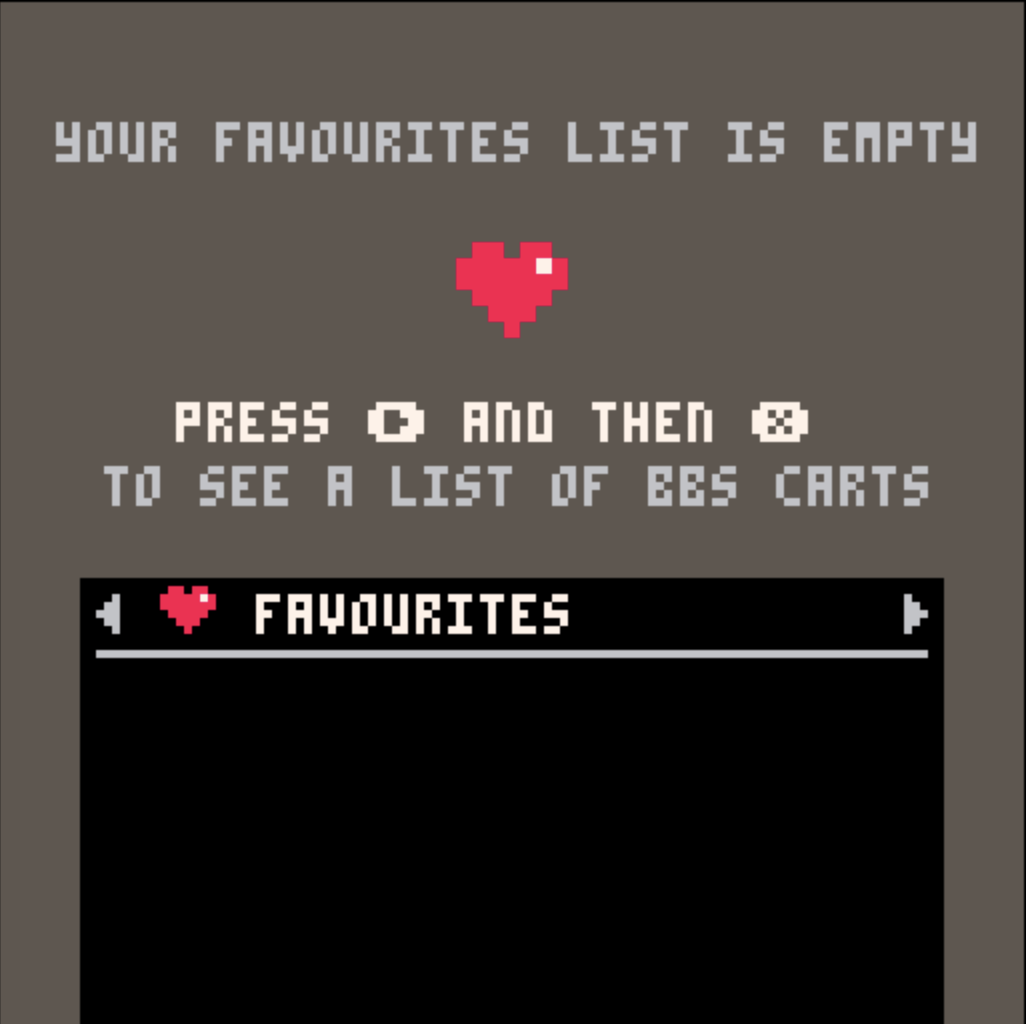

Don’t think of Pico-8 as a game. The creators call it a “fantasy console” which is just fancy talk for a “pretend retro console”. Instead, you should think of Pico-8 as if it were the development software to make games for an old console like the NES. When you first run the executable, you are greeted with a potentially ominous looking command line that might have even loaded into a fullscreen experience. There’s a bit of text at the top a > and a flashing block. The only thing you are given is “TYPE HELP FOR HELP” (I’m not yelling at you, the program renders all lower-case letter as capital, and renders entirely different characters if you hold shift and type). Naturally, you should type “HELP”. This gives you some of the basic commands that you should need to know to operate the program. While reading through, you see a line with a different color to it.

There’s only one thing you can do at this point.

You continue to follow the text on the screen, and are met with a list of games.

At this point, you should start exploring. The controls will start to come, each game uses them a little different, but for the price of $15, you are able to explore so much of what human creativity has to offer within the games space. It becomes a treasure hunt. Maybe you find a tech demo exploding with color. Maybe you find a short puzzle game. Maybe you find someone’s first attempt at making a game altogether. Maybe you a demake of a classic game like Doom or WarCraft. The possibilities are truly endless. All these games were made by other people who love games and art and, more importantly, people who love sharing their art.

All the games within Splore are free to play, free to download and keep. Technically, you don’t even need the Pico-8 software installed in your compute to play these games. Many of these games are available to play for free on websites like Itch.io when you search for “Pico-8” as a tag. These game run so well, they’re simply embedded in the browser. However, one of the fun experiences for young and old alike is the recreation of the classic DOS-era console-focused interface of times long past.

Why you should get and make Pico-8 games

Advertising Pico-8 as simply a bit of software that gets you free games is selling it short. In reality, Pico-8 is a game engine. It’s a bit of software that comes with a text editor, a sprite editor, a background editor, a sound generator, and music creation suite all in one: everything you need to create a retro-styled game, all in a single location. On the command prompt screen, pressing ESC opens the text editor window, immediately dropping you into the window into the game you’re supposed to make.

Games are written using Lua syntax, but you’re going to have better luck searching how to do things specifically in Pico-8. There’s a well documented set of functions that are used to perform any action from drawing a circle or drawing a circle, or to triggering specific sound effects and playing songs. All the precise details can be found in the manual provided by the creators of Pico-8. Additionally, there are sub-reddit and discord communities that would be more than willing to answer any questions you may have about the software and how to perform certain actions. I can’t exactly speak to how accessible Lua and the Pico-8 API are, but I can say it’s not going to be any harder than programming in any other game engine or programming language. One of the big benefits it has however is the fact that you only pay $15 and you can make and create as many games as you want. I can say that no other game engines are going to be any easier to get into. I can also say that it requires just about no actual hardware specifications to run the games (read below where I talk about raspberry pi). If you have a computer than can boot into an operating system (not including smartphones or tablets), you have a computer that is capable of building and running Pico-8 games.

Why you should join the community around making small games

I haven’t gotten around the making a game in Pico-8 specifically; Lua isn’t my preferred programming language. Making games isn’t something that naturally comes to me. I love to build a physics engine that is able to compute a bunch of math very quickly, but graphics, music, and story are just not things that naturally come to me. Make it worse, I haven’t had the time to invest into developing those skills, nor much of the desire. One of the things I would love to do however, is help make a part of the game.

Itch.io sponsors what they call “Game Jams”. These are short sprints to make a game. Typically they follow some theme around an idea to inspire new game ideas, or restrictions where you have to make a game using a specific software. I love checking out the small little games that are made in these jams, again, just to see the creativity of humans all around. Pico-8 is the perfect engine to make a quick game that’s small in size, can be embedded into the webpage for your submission, making playing the game and getting voted for super easy, and the files are easily sharable among your friends or family, if you decided to work with other people to make games. Most importantly, it’s a quick and easy way to get talking to other people about their ideas and how they did certain things. These people are always super chill, and sometimes they have giant youtube channels that host jams that receive thousands of submissions.

Why you should get it and install it on all your computers

Remember how I said you can put it on just about every computer? I meant it. It has a build for every major operating system: Windows, MacOS, Linux, and my personal favorite build, raspberry pi. Those 90 computers have a version just for them. I won’t go down the rabbit hole of why you should check our raspberry pi as a computer, but one of my favorite things to do with them is turn them into retro game consoles. They can run emulators, connect to wired or bluetooth controllers and play all the classics from the NES to about PS1. On top of that, you can also add in the executable for Pico-8, and now it’s also an emulator for a console that never actually existed. Set it up to automatically boot into the Splore menu, and you basically have an internet connected console that download any game you want from it. This can also include those small hand held retro game emulation devices. You know, the ones TikTok Shop pushes from Ambernic and Miyoo? I did this with mine and it worked great, right up until I lost that console. At the end of the day, it’s a game console, it’s a dev kit, it has a lot of functionality, even some that the developers probably never anticipated it would have.

Maybe some reasons you should pass on Pico-8

Let’s assume for the sake of discussion that you already know you want to get into making video games. I believe Pico-8 is a wonderful low-barrier way to get into making games. That being said, there’s a lot of limitations to the environment. If you’re looking at some specifications about Pico-8 (as it sits as a console), you will likely see things that look a little funny like like a display size of 128x128, or only 16 colors, or 32 kilobyte carts. Back on the topic I mentioned above where Pico-8 is treated like a retro console that never actually existed. These seem very small, especially when considering that current games have a minimum of 1280x720 and can balloon up to +100 GB in size. These limitations are intentional to encourage a specific experience. In their own words,

The harsh limitations of PICO-8 are carefully chosen to be fun to work with, to encourage small but expressive designs, and to give cartridges made with PICO-8 their own particular look and feel. (PICO-8 Fantasy Console)

The point of Pico-8 is to create a very small games: Small in scope, Small in size, small in effort. Most of the games I’ve played with are short experiences, arcade like experiences, or even following the pattern of mobile games, with 20-30 short puzzle box levels. I’ve seen a couple that have a full runtime of up to an hour or so, with a full upgrade path arc. They have never been on the level of Children of Morta, CrossCode, Halo, Skyrim, or even something like Shovel Knight. The closest exception would be where Celeste started out as a game on Pico-8, but was eventually transformed into a full game. But these full sized games aren’t the point. The point is quick prototypes, fast development cycles, fast playtimes, and sharing. If these are not restrictions you are willing to work in, then maybe pass this one up.

Get it anyways

You should get Pico-8 anyways. It’s a great tool to get some creative juices flowing. It lets you test out ideas in game games just to see if something is fun. It can always be extracted and fleshed out in a full game engine when relevant, but as a quick thing to work on, it’s great fun. It also is a great game discovery console when connected to the internet. Get a copy for yourself. Let your kids play it. Help your kids make their own games with it. Allow them to flex their creative muscles, learn a new skill, think critically, and solve problems.

Links:

Main website: https://www.lexaloffle.com/pico-8.php Itch.io: https://lexaloffle.itch.io/pico-8

Alternatives

While Pico-8 has the largest community by far, there are a handful more fantasy console that exist, some made by the same people that made Pico-8. Here are some that I find interesting. The one I find most intersting is Tic-80. It follows almost the exact same patterns as Pico-8 with tools built into the software, a “surf” feature to find new games, and a command line interface used for navigating within the software. This one has a free-teir, with some useful features behind their cheaper $10 price tag. It also supports other language syntax like python, ruby, and javascript, in addition to Lua, and several others. The main difference is that this game feels more DOS like, where as Pico-8 feels more an NES. Check out this one for a quick test to see if you hate the idea altogether and are nervous about spending $15.